April 17, 2005

'The Outlaw Bible of American Literature': The Rebel Establishment

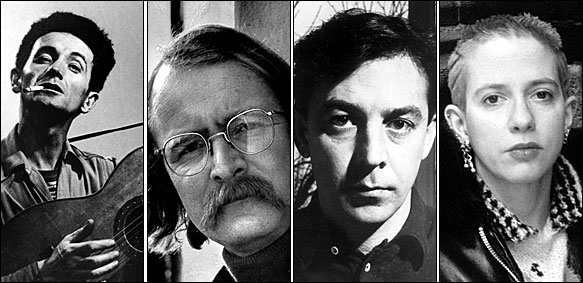

From left: Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Vernon Merritt III/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images, Hulton Archive/Getty Images and Jerry Bauer

From left: Woody Guthrie , Richard Brautigan, Terry Southern and Kathy Acker.

|

By DAVID GATES

|

THE OUTLAW BIBLE OF AMERICAN LITERATURE Edited by Alan Kaufman, Neil Ortenberg and Barney Rosset. Illustrated. 662 pp. Thunder's Mouth Press. Paper, $24.95. |

![]() ack in the late 1930's, when Philip Rahv made that famous distinction between American literature's ''redskins'' (yawping Walt Whitman) and ''palefaces'' (finicking Henry James), he was talking about contrasting sensibilities, not armed camps. But in the 50's, all hell broke loose. With the publication of ''On the Road,'' ''Howl'' and ''Naked Lunch,'' the Beat writers and the establishment (which might have been smug enough not to have realized it was any such thing) declared war on each other, and the Beats were cast -- and certainly cast themselves -- as the rebel-angels of a perpetual insurrection, recruiting from beyond the grave (Blake, Rimbaud), trying to enlist neglected, potentially sympathetic elders (Pound, Williams) and potential fellow travelers (the Black Mountain school), proselytizing the young. Earlier American misfits, from Melville through Robinson Jeffers, had probably figured neglect was just their personal tough luck. Now misfits had a movement, even if they were too cantankerous to sign up: a literary counterculture with an alternative -- at heart, a Miltonic -- reading of literary history. The entrance exam was largely a background check, and nobody graded the written portion.

ack in the late 1930's, when Philip Rahv made that famous distinction between American literature's ''redskins'' (yawping Walt Whitman) and ''palefaces'' (finicking Henry James), he was talking about contrasting sensibilities, not armed camps. But in the 50's, all hell broke loose. With the publication of ''On the Road,'' ''Howl'' and ''Naked Lunch,'' the Beat writers and the establishment (which might have been smug enough not to have realized it was any such thing) declared war on each other, and the Beats were cast -- and certainly cast themselves -- as the rebel-angels of a perpetual insurrection, recruiting from beyond the grave (Blake, Rimbaud), trying to enlist neglected, potentially sympathetic elders (Pound, Williams) and potential fellow travelers (the Black Mountain school), proselytizing the young. Earlier American misfits, from Melville through Robinson Jeffers, had probably figured neglect was just their personal tough luck. Now misfits had a movement, even if they were too cantankerous to sign up: a literary counterculture with an alternative -- at heart, a Miltonic -- reading of literary history. The entrance exam was largely a background check, and nobody graded the written portion.

That's a short version of the history behind ''The Outlaw Bible of American Literature,'' a new anthology put together by the writer Alan Kaufman, the editor Neil Ortenberg and the seminal publisher Barney Rosset, whose Grove Press and Evergreen Review gave a brand -- and more important, a home -- to writers once deemed, for whatever reason, too dangerous to handle. Some of the foreigners Rosset supported (Beckett, Pinter, Ionesco) have long since become respectable, if no less formidable. But most of the Americans he published (William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Terry Southern) remain outsiders. In part this is because of the work itself: sometimes semipornographic -- though seldom gamier than passages in John Updike and Philip Roth -- sometimes antiestablishmentarian, sometimes hard to read, sometimes all of the above. But in part it's because the idea of literary outlawry -- any kind of outlawry -- is irresistible to the American imagination, which may never outgrow its Puritan-Manichaean origins. In fact, for two cents, I'd say ''The Outlaw Bible'' is a quintessential document of the Bush Era, but that would hurt everybody's feelings.

At any rate, although the Rosset-sponsored rebels of the 50's and 60's center this collection, the editors have opened the countercanon wide to take in a full range of American Unclubbables. Mickey Spillane, Sapphire, Waylon Jennings, John Waters, Greil Marcus, Margaret Sanger, Dave Eggers, DMX: you won't find all of these people together in any other book, ever. (The only folks not invited to the party seem to be the far-right cranks: the militiapersons in ''The Turner Diaries'' may be extralegal, but they're not outlaws.) It's just what an anthology of alternative/outsider literature ought to be: all over the place. You can read Woody Guthrie on hopping freights, Valerie Solanas on cutting up men and Emma Goldman on doing prison time. As long as you're not expecting that all these writers can write, there's no reason you shouldn't have a good time.

But ''The Outlaw Bible'' is supposed to be good for you, and that's what changes it from an entertaining miscellany to something worth thinking about. Depending on where you sit, it's either a document recodifying a revolution or a relic recyling an obsolescent controversy. The editors' introduction, of course, argues for its contemporary relevance: ''a revolt against a landscape dominated by a literary dictatorship of tepid taste, political correctness and sheer numbing banality.'' Your reflexive reaction is to leap to your feet, whet your knife and take the tarp off the old tumbrel -- the problem with numbing banality is, it doesn't numb you enough -- but then you remember what year it is. True, goon squads of editors and critics still keep the frightened masses buying superficially quiet fiction about superficially quiet people by Alice Munro and Marilynne Robinson. But some of the writers the regime is now grooming to take power look a lot like insurgents themselves: indecorous, sometimes indecent, not snobby about pop culture. Whatever you think of David Foster Wallace or Michael Chabon, Gary Shteyngart or Jonathan Safran Foer, they're more mermaid than Prufrock. For every current big-name writer who's flatlining, I can name you one who's redlining. (But not here. We'll talk after the show.)

Kaufman and his fellow editors seem to be fighting battles that were over with half a century ago -- in romantic-sentimental language that should have been over with half a century ago. ''Some of our best, our fiercest, our most volcanic prose,'' they write, ''is not a tongue-twisted Henry Jamesian labyrinth of 'creative writing' but an outraged American songline of tear-stained revelation.'' I can't sit still for James either -- who the hell can? -- but the editors ought to visit some creative writing classes: these days, both Jamesian maundering and Vesuvian spewing get the red pencil. And the attempt to transplant bebop-era grievances to a hip-hop world -- ''in the grip of Google and Wal-Mart'' -- only makes them sound clueless. This alternative canon, they write, springs ''not from reality shows, Botox or I.P.O.'s, but the streets, prisons, highways, trailer parks and back alleys of the American dream.'' Jeez, why pick on Google, the most useful tool since the stone ax? (That's how I found out it was Rahv and not Lionel Trilling or somebody who'd thought up the paleface/redskin thing. Took me 30 seconds.) And if you're all about the trailer park and the prison, why dis Wal-Mart, which melds the two so perfectly that writers should stop wishing it away and start hanging out there and taking notes?

''The Outlaw Bible'' may be an uneven reading experience -- after reprinting that bit of Bob Dylan's ''Tarantula,'' the editors have their nerve to complain about tongue-twisted labyrinths -- but it makes an absorbing exercise in taxonomy. Who exactly qualifies as an outlaw and why? Let's try a little quiz. Without looking at the table of contents, which two made the grade?

A) Bret Easton Ellis

B) Norman Mailer

C) Grace Paley

D) Raymond Carver

Time's up: B and C. Mailer qualifies because he's ''walked a tightrope over public opinion, often with a dagger in his teeth'' -- possibly an allusion to his stabbing his wife all those years ago? -- for his ''hipster manifesto 'The White Negro' '' and his ''literary sponsorship of the criminal Jack Henry Abbott'' (who's also in the anthology). Paley has published ''highly acclaimed collections of short fiction,'' but heck, so has Munro. Selling point: her antiwar, antinuke and feminist activism. So what's wrong with Ellis and Carver? If you read carefully the stuff I quoted above -- I can't blame you if you skimmed -- you'll see why they don't belong in the club of those who don't belong in the Club. Patrick Bateman in Ellis's ''American Psycho'' is far more crazed and violent than Stephen Rojack in Mailer's ''American Dream,'' but he's an I.P.O. kind of guy: out. Carver passes the trailer-park test, but his flintlike precisionism doesn't fit the lava-flow aesthetic. Outlaws are not anal.

Now that you understand the rules, here's Round 2. None of these writers made it into ''The Outlaw Bible,'' but two of them might have. Again, pick the outlaws:

A) Charles Bukowski

B) Susan Sontag

C) Jim Bouton

D) Ernest Hemingway

You're catching on: A and C. Sontag's politics are O.K., but she had that mandarin thing happening: forget it. An outlaw can't be a fancy pants. Hemingway gets points for his suicide and his slumming -- check out that story ''A Pursuit Race''; it's got a guy shooting dope -- but precisionism and the Nobel Prize are deal-breakers. Bukowski? Absolutely: working-class boozer, volcanically prolific, neglected except for a cult following. Bouton? A borderline case: I threw him in to make it interesting. In ''Ball Four,'' he admits he was ''too chicken'' to take the acid hippies offered him in Haight-Ashbury. But any writer subversive enough to have the baseball commissioner tell him he'd ''done the game a grave disservice'' -- and then to use the quotation on his book jacket -- ought to get the benefit of the doubt. Mailer himself once did the pans-as-blurbs thing in an ad for ''The Deer Park.''

If you believe the editors' introduction, what makes an outlaw writer isn't the writing but the life. ''The authors in this collection are not greeted with book club invitations'' -- take that, Jonathan Franzen -- ''and White House invitations.'' (In fact, by my count, four of the contributors were invited to the White House at one time or another, and they went like lambs; the excerpt from Dick Gregory's autobiography even tells about it.) Rather, these writers ''often lead lives of state pen incarceration'' -- rhymes with quiet desperation -- ''street hustling, exile, martyrdom, and even murder at the hands of strangers. . . . William S. Burroughs . . . traveled to the edge of heroin addiction and preserved in deathless prose what he found there. . . . Iceberg Slim . . . ran whores before turning his hand to books. . . . Ken Kesey . . . captured the American heart in great epic novels before transforming its society through Merry Prankster revolution.'' Understand, I have nothing against heroin addiction, running whores or transforming society -- it's all good -- but I wonder about the tacit assumption that such experiences make your tear-stained prose sing. Wouldn't revision be less time-consuming and involve less wear and tear? And the four writers who get special mention -- Richard Brautigan, Breece D'J Pancake, Donald Goines and F. X. Toole -- are specifically singled out for having died: the first two by suicide, Goines by murder, Toole a year after his only book appeared. This may be too Zen to get your head around, but I'm tempted to think that not living long enough to write anything at all might be a literary outlaw's savviest career move.

I'm also tempted to make a really snarky transition here. But let's just say that some of the old obligatories in this anthology -- the canonical noncanonicals -- are starting to show their age. The scene in Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg's ''Candy'' in which the heroine is seduced by a hunchback -- ''With a wild, impulsive cry, she shrieked: 'Give me your hump!' '' -- must have been campy titillation four decades ago. Now it's a museum piece: soft-porn whimsy half a cut above Playboy's ''Little Annie Fanny.'' Better to concede that it used to be a big deal and skip the actual experience. The seven-page excerpt from Henry Miller's ''Tropic of Cancer'' -- in a Paris bordello, a Hindu friend of Miller's na´vely defecates in the bidet -- proves to be an endurance test whose only reward is a grade-B aphorism: ''For some reason or other man looks for the miracle, and to accomplish it he will wade through blood.'' On the other hand, the two pages of Iceberg Slim's ''Pimp'' still have a blunt force; even the musty slang -- ''swipe'' is not a verb; ''cat'' is not an animal -- doesn't soften the claustrophobic, heartless menace. And familiar passages from Burroughs's ''Junky'' (''Bill Lee'' tries to kick morphine but kindly Old Ike helps him backslide) and Kerouac's ''On the Road'' (na´ve Sal Paradise first meets holy motormouth Dean Moriarty) seem as fresh, direct, involving and un-arty as the first time you read them: at their best, these two are redskins fit to go up against the best the palefaces had to show.

The more recent outsiders could also give the respectables a run for their money. This may ruin Michelle Tea's Sunday, but how could you improve on this passage from ''The Passionate Mistakes and Intricate Corruption of One Girl in America,'' with its mix of strangeness and photographic specificity? ''I was up with the sun in the toxic gold of my bedroom. It took 12 cans of spray paint to make the walls glow like that, my trigger finger cramped and sticky and I blew my nose gold for a week.'' And the late Kathy Acker won my heart years ago with the beginning of her 1982 novel ''Great Expectations.'' (''My father's name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Peter.'') This isn't to say I can read her books all the way through -- she once said she never expected it -- but in short takes she can be brilliant. Here's part of the excerpt in ''The Outlaw Bible'' from her novel ''Don Quixote'':

''I think Prince should be president of the United States because all our presidents since World War II have been stupid anyway and are becoming stupider up to the point of lobotomy and anyway are the puppets of those nameless beings -- maybe they're human -- demigods, who inhabit their own nations known heretofore as 'multinationals.' On the other hand: Prince, unlike all our other images or fakes or presidents, stands for values. I mean: he believes. He wears a cross. . . . Prince believes in feelings . . . and fame. Fame is making it and common sense.''

Dreadful writing? Acker is well aware of that -- she's careful to let us know she's done her tour of the literary canon -- and she revels in her transgression against competence and in the Gertrude Stein effects she gets when she's just blurting (''Fame is making it and common sense''). And anyway, this is a persona: a voice brutalized and rendered inarticulate by the same political and cultural mediocrity and mendacity it's railing against. Over the top? Discrediting her own case? Brilliant of you to notice. But it's part of her strategy to affront responsible people. You may not like it -- she doesn't want people like you to like it -- but you can't say it's not sophisticated.

Some of the best moments, though, come from the contributors with no literary pretensions at all, just telling yarns, doubtless channeled by ghostwriters. In ''The Godfather of Soul,'' James Brown writes about hearing a knock on the door of his hotel room and finding a grenade with his name painted on it. ''I'd seen enough grenades in prison and in Vietnam to know it wasn't live, but it was the thought that counted.'' And the selection from Waylon Jennings's autobiography has the Platonic country-music anecdote, about Hank Williams:

''Faron Young brought Billie Jean, Hank's last wife, to town for the first time. She was young and beautiful, and Hank liked her immediately. He took a loaded gun and pointed it to Faron's temple, cocked it, and said, 'Boy, I love that woman. Now you can either give her to me or I'm going to kill you.'

''Faron sat there and thought it over for a minute. 'Wouldn't that be great? To be killed by Hank Williams!' ''

I'm with the levelers on this one. That's not literature? All right then, I'll go to hell.

Maybe in a hundred years, assuming there's anybody left around, people will be amused at their great-grandparents' failure to grasp the self-evident idea that what was called literature was a niche-marketed intellectual property, and that the war between the outlaws and the canonicals was another dispute between Big-Endians and Small-Endians. (Half a dozen people with a taste for the recherché will even get the allusion.) You can already see the borders getting porous. Final quiz: where do you put A) Mary Gaitskill, B) Nicholson Baker, C) Neal Stephenson, D) Jonathan Lethem? Canonicals or alt.canonicals? Or should we call them, along with Foer, Wallace and so on, postcanonicals? (Just plain ''writers'' would put the taxonomists out of business.) ''Don't join too many gangs,'' Robert Frost advised us back in 1936, but for the past 50 years or so, writers haven't had much choice: who you hang out with, and who watches your back, defines what you are. ''The Outlaw Bible'' still posits a literary East L.A., with palefaces and redskins tagging and throwing up signs. With a little luck, we won't have to live here much longer.

David Gates is a senior editor at Newsweek. His most recent book is ''The Wonders of the Invisible World,'' a collection of stories.